Actionable strategy: Connecting your vision with your day-to-day work using OKRs

A strategy for a for-purpose organisation is a tool to help you make clear, intentional choices to create the positive impact you want to achieve using the resources you have available.

Unlike in the corporate world, where strategy often focuses on market differentiation or beating competitors, strategy in the for-purpose sector is more about:

Clarifying your purpose and goals: What change are you trying to create?

Aligning your activities: Are your projects and programs actually contributing to that change?

Adapting to your environment: How can you respond to the evolving needs of the community you serve?

A good strategy should help your team make better decisions, prioritise what’s important, and stay focused on your mission. It’s not just a statement for the board or a fun diagram — it’s a way of navigating complexity and uncertainty while staying true to your organisation’s purpose.

In short, strategy is the story of how your organisation makes a difference and a way to ensure that everyone is pulling in the same direction toward that shared goal.

In the sector, strategy is often takes the form of a lofty aspiration, or a wishlist of outcomes and initiatives. But the best strategies go deeper. They bridge the gap between strategy and day-to-day work is about creating a hierarchy that connects and creates coherence at each level.

Let's break it down.

The levels of strategy: creating a connected and coherent strategy

One of the first things I ask for on any project is a copy of the strategy. Over the years, I’ve seen some great ones — strategies that truly help guide decision-making — but I’ve also seen plenty that have their heart in the right place but aren’t actually helping anyone make tough decisions.

Generally, the issue comes down to a lack of differentiation between the levels of the strategy. We’ve all seen those “strategy on a page” documents, with neatly arranged boxes filled with aspirations and outcomes. These documents are often wordsmithed to the point of saying very little. They can end up being repetitive, unclear, political, and ultimately not very useful.

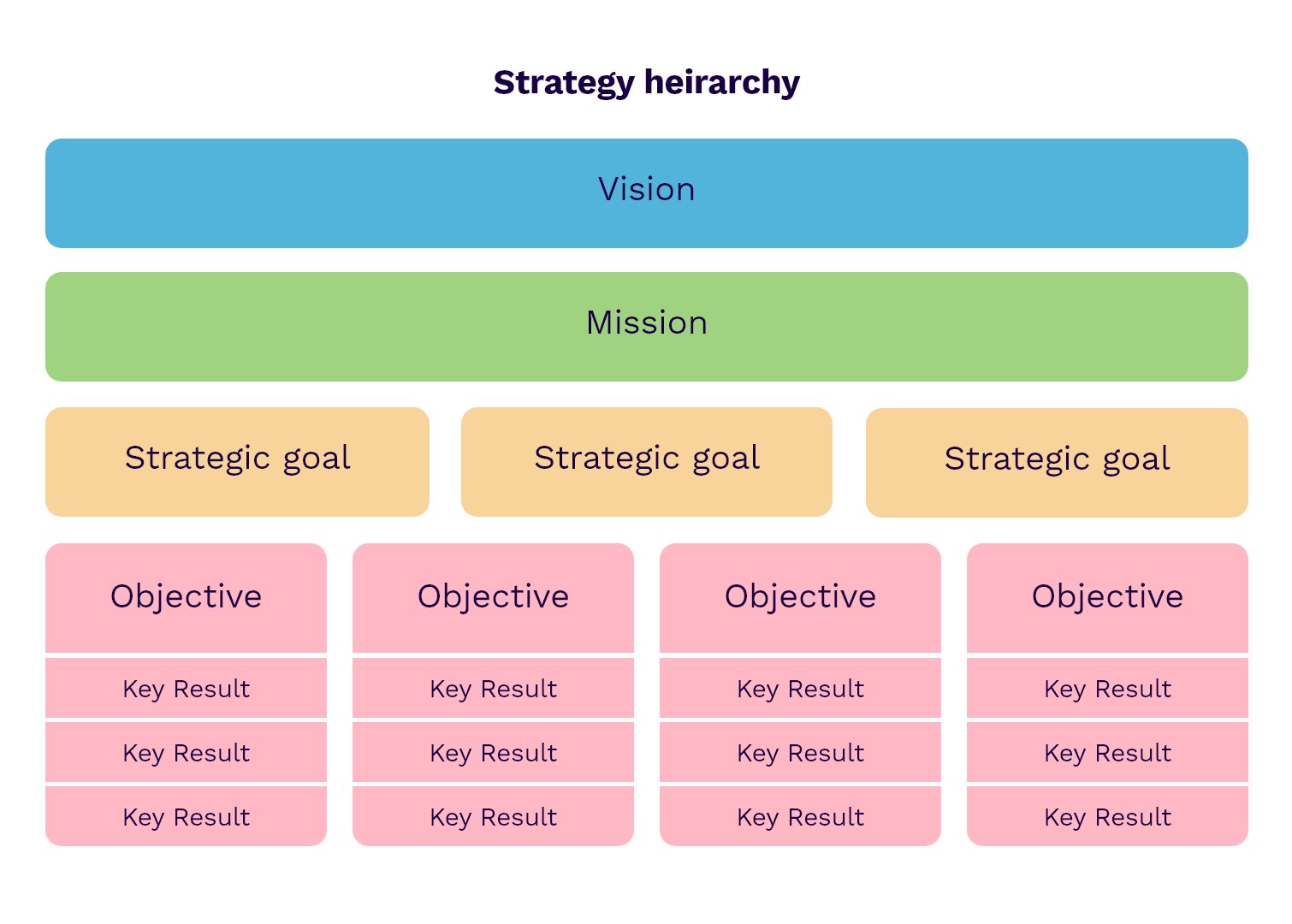

The best thing you can do to ensure that your strategy is actionable is to make sure it has a clear through line from your high-level mission or vision (which stays constant) to strategic goals (which take years to achieve), down to short-term objectives and measures (which can be delivered in about a quarter) and projects or initiatives that deliver those objectives.

If your strategy clearly connects each of these levels, it won’t just sit on a shelf. It will become a tool to help your team prioritise, make decisions, and focus on what matters most.

Here’s a breakdown of common levels:

Vision and mission

Defines the long-term impact and future you want to create.

Provides a North Star to guide strategic and operational decisions.

Strategic Goals

Articulates the key focus areas and challenges to address.

Breaks the vision down into key focus areas with a view on how we might move closer to it.

Objectives and Key Results

OKRs

Break down strategic goals into actionable objectives that are completable within a set timeline.

Helps measure progress toward strategic goals.

Projects/Programs/ initiatives

The specific work that needs to be done to achieve the OKRs

Turns strategy into tangible actions.

Note: The names of these levels tend to vary from organisation to organisation, and there’s no one-size-fits-all template. Think of this as an approach to connecting long-term aspirations with on-the-ground actions, rather than a rigid framework.

It’s also likely your organisation has values or principles that underpin everything. These serve as guiding foundations and can often be treated separately from the strategy itself.

Why levels help

The idea of a 5-year strategic plan is dead — or at the very least, on life support. The pace of change and growing complexity in the world means that static, long-term plans no longer cut it. Instead, we need to take a more systemic approach that allows for trial, validation, and iteration. Rather than mapping out a rigid 5-year plan, using levels and setting shorter-term goals like OKRs gives you the flexibility to adjust as needed while keeping your long-term vision in mind.

This approach is about being responsive to change without being reactive or volatile. It’s about balancing adaptability with stability, so your strategy can evolve with the world around you. By introducing hierarchy and levels, your strategy will stay front of mind and alive rather than becoming something that just sits on a shelf. It becomes a daily tool for making resource prioritisation decisions and a way to connect today’s actions to the future you want to create.

It helps people see that what they’re doing right now matters — and how those efforts are contributing to a bigger, shared vision.

Set a clear vision of the change you want to create

Your vision is your organisation’s North Star — a long-term, aspirational statement that describes the future you want to help create. It should clearly articulate the change you want to see and who it’s for.

For example:

“Create a world where no child goes to bed hungry.”

Is it lofty? Yes, a little. But it’s also specific and clear. Compare that to something overly generic like:

“Create a better world for our children”

That could mean anything. The key is to strike a balance. It’s not about perfection, but your vision should articulate the change you want to see and who it’s for.

It’s also useful to have a mission statement that clarifies how your organisation plans to create that change.

For example:

“We are committed to ending childhood hunger. In the U.S. and around the world, we provide children and families with the food and essentials kids need to grow and thrive.”

Some organisations choose to keep their vision and mission as separate statements, while others combine them into a single guiding statement. Both approaches are fine — what matters most is clarity.

At some point in your strategic documents, you need to articulate your specific role in achieving your vision. This clarity will help with prioritisation later, ensuring that your organisation’s resources and efforts are focused on what truly matters.

But we already have a vision

Organisations tend to spend a lot of time crafting vision statements. And once they’re set, they’re usually hard to change. The good news is, that’s not typically where the problem lies when it comes to strategy.

Most of the time, the vision is solid and workable. The real challenge comes in connecting that vision to the day-to-day work. It’s about making sure that what people are doing today is contributing to the future your organisation wants to create — and that’s where many strategies fall short.

Break the vision down into strategic goals

Strategic goals provide a diagnosis, insight, and point of view on the challenges your organisation faces in achieving its vision. They act as a bridge between the vision and the work on the ground, guiding what needs to happen to move from the current state to your future vision. Think of it this way: What is your hypothesis of the work that needs to be done to achieve your future vision?

The number of strategic goals will depend on the size and complexity of your organisation. In some cases, you might need to group goals into themes or categories. What’s important is that each goal outlines a point of view and a way forward.

These goals should be built on research and learning from those on the ground. They aren’t just aspirations; they are hypotheses about what needs to be done to create the future you’re working toward.

A great strategic goal includes:

Insight or diagnosis: What’s happening right now? What’s holding people back or driving the challenge?

Point of view on how to respond: What do you believe needs to happen to create positive change?

Clarity on what you want to achieve: What’s the intended outcome, while leaving room for different approaches to get there?

An issue I see a lot is that strategic goals are either:

Too high and lofty — essentially just a bunch of additional vision statements, or

Too tactical and prescriptive — where they simply describe key programs or departments.

Your strategic goals should act as the connective tissue between your vision and your programs and short-term goals. They need to be specific enough to provide direction, but broad enough to allow flexibility in how the work gets done. This is the layer that links your aspirational vision with on-the-ground actions, ensuring your strategy is both inspiring and practical.

For example:

“Create partnerships with local organisations, government agencies, and communities to increase sustainable impact while affirming the dignity and agency of individuals and families.”

Let’s break down the example goal:

Insight (Diagnosis)

Many traditional aid models can unintentionally undermine the dignity and agency of the people they’re trying to help by making them passive recipients of support. Additionally, efforts can often be duplicated or fragmented, leading to short-term fixes rather than sustainable solutions.

Point of View (Response)

To create sustainable, lasting impact, we need to work in partnership with local organisations, government bodies, and communities. This approach ensures that those who are closest to the issue are leading the change. Partnerships should be built on respect and mutual trust, affirming the dignity and agency of the people involved, rather than imposing external solutions.

Break the goals down into short-term objectives

Objectives and Key Results (OKRs) are a great way to get really specific and connect goals to projects. Identifying and prioritising OKRs for a period — normally 3 to 6 months — really helps create focus.

This is the area I see making the most direct impact on strategies in for-purpose organisations. It’s the missing link between strategy and operations. Too often, organisations have a list of projects and initiatives on one side, and a strategy that’s on the other, completely disconnected. OKRs bridge that gap.

But what are they?

They’re the specific things you want to achieve during that time frame. The objective outlines what you want to complete, and the key results are how you’ll measure whether you’ve achieved it.

Example OKR:

✅ Objective: Create the foundations for local partnerships

📏 Key Results:

Conduct a landscape review for potential partners in priority areas

Have 30 conversations with partners and their networks

Identify and engage 10 local organisations or agencies as potential partners.

Understand and share learnings about what affirming dignity and agency means for these groups

Co-design a partnership approach

How OKRs work

Each quarter, you set about four OKRs (though this can change depending on the size and complexity of your organisation). You might have portfolio-level OKRs or department-specific OKRs, depending on how you work.

OKRs can be linked to specific projects, or they can be used as a brief to guide new initiatives.

Once your OKRs are set, you track progress over the allocated period. They provide a shared language to check how things are going. At the end of the period, you reflect on what worked, what didn’t, and set new goals for the next cycle.

In short, OKRs help your organisation stay focused, flexible, and accountable. They keep your strategy alive by breaking it into manageable pieces and making sure progress is visible to everyone involved.

Deliver on these objectives through projects and initiatives

The final layer is projects, programs or initiatives. Projects and programs are the vehicles for delivering OKRs. They represent the day-to-day work that drives your organisation forward.

Every project should align with an OKR and contribute to a strategic goal. If a project doesn’t align, it’s time to ask:

Why are we doing this?

Is it a priority?

Does it help us move toward our vision?

Which brings us to prioritisation.

Prioritisation

A lot of clients ask me for a prioritisation framework. They’ll say things like:

“We’re stuck.” or “We can’t make decisions.” or “We keep relitigating projects over and over.”

When I hear this, it usually tells me there’s a missing connection between the vision and the work to be done.

While there are lots of prioritisation approaches — from complex multi-factor scoring systems to simpler collaborative processes — none of them will work well without a clear strategy. Your strategy needs to break down into strategic goals and short-term objectives that clearly outline what’s important. Without this clarity, prioritisation becomes messy and subject to personal opinions or politics.

So, if you’re having trouble prioritising, take a step back and look at your strategy. Ask yourself:

Does our strategy make it clear what we should and shouldn’t be spending our energy on?

If the answer is no, it’s time to work on ensuring that the different layers of the strategy are all in place and doing what they need to do. When each layer of your strategy is aligned and clear, prioritisation becomes a lot easier — because the choices you need to make will be obvious.

The good news

If all of this is ringing true, I’ve got some good news for you.

First, this is really common in the for-purpose sector. That’s not an excuse to leave it unfixed, but it does mean you’re not alone. Many organisations struggle to connect their long-term vision to what’s actually happening on the ground.

Second, you probably already have many of the ingredients for a connected and coherent strategy. The knowledge likely exists across your organisation — it’s just about bringing it together and making those connections visible.

Finally, the shift away from giant 5- to 10-year strategies toward more evolving, iterative strategies makes this a lot less daunting. Not only are evolving strategies more effective — because they allow you to act in a more systemic way, responding to change as it happens — but they also help make your strategy more inclusive and participatory.

There was a time when organisations would launch a new strategy, and people who didn’t connect with it would disengage for the next five years, retreating into silos. Now, OKRs can be a great conversation starter. OKRs don’t — and shouldn’t — last forever. You can encourage debate, invite challenges, and introduce new OKRs each quarter. This ongoing process keeps people engaged and makes them feel like they’re contributing to the evolution of your strategy.

An evolving strategy isn’t just more responsive — it’s more engaging, participatory, and human.